- Home

- Tony Roberts

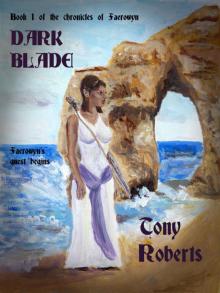

Dark Blade

Dark Blade Read online

DARK BLADE

The First Tale Of The Chronicles of Faerowyn

© Tony Roberts 2015

www.tonyrobertsauthor.com

ISBN 978-1-5136-0445-9

Artwork by Jane Vellender

Table of Contents

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

TEN

ELEVEN

TWELVE

THIRTEEN

FOURTEEN

FIFTEEN

SIXTEEN

SEVENTEEN

EIGHTEEN

Also by Tony Roberts

ONE

The wind blew in off the ocean, salt laden, stinging the face of the lone figure standing on the sandy shore. The sea spray, mixed with the fine, gently falling rain, melded with the tears running down her face so that anyone who would see her would not be able to tell what was what.

She cared little for herself; her grief consumed her. What did it matter that it was raining, or that the wind was blowing the tops of the small waves in the cove at her? She was wet through but it didn’t matter. Nothing mattered. Save her sense of loss.

Her mother had hung on resolutely, defying death until the girl’s sixteenth birthday. That had been yesterday. Birthdays should be celebrated, but Faerowyn’s sixteenth had not been one to do that. Her mother had finally succumbed halfway through the day, a wasted shell of what she had been, a remnant of the person Faerowyn had known. The wasting disease was not one that spared anyone, and her mother had been no exception.

Her last words to the girl had been faltering, whispered ones of apology. Apology for what? Bringing her up with no father in some isolated fishing village at the far end of the known world? Staying in a place where the locals resented her presence, so that she had grown up shunned by the majority of the narrow-minded traditionalists who lived there? Sorry that she had never told Faerowyn about her father, who he had been, what he had been? Regret that Faerowyn had been deliberately denied all knowledge as to whom and what she was?

Now her mother was dead and the only person who could have satisfied her frustrated curiosity was gone. Not only that, for there was now the other chilling fact that there was now nobody who wanted her here. For so many years Faerowyn had been the object of snide comments, cruel jibes, fun poked at her by her contemporaries. ‘Half-breed’, ‘elf spawn’, ‘mud-face’ and so on.

Faerowyn’s skin was dark, much darker than any of the people here in the village of Selanic, the place of salt. Her flesh was almost as dark as the bark of the slow-growing trees that grew on the hills behind the village, those hills that virtually cut off Selanic from the rest of the countryside. The only way to effectively come to and leave the place was by sea, and as it was so isolated and far away from the trade routes, ships did not come that often for it was not commercially viable for them to do so. The only thing that did bring ships was the salt trade, something the village was good at. The sea here was shallow and left pools at high tide which evaporated during the summer heat, leaving huge deposits of salt behind.

Locals had learned over the centuries to scoop this up before the tide returned and to store it and fashion it into pillars to either use or trade with.

Faerowyn was not interested in that. She was interested in her heritage. Why was it that she had dark skin, slanted dark eyes, slender, pointed ears? Elf spawn? What did that mean? She had asked her mother and a few others in the years gone by but had received no response. Eventually she had come to recognise something odd when people looked at her, something as a child she could not possibly have known. But now she did see it, and it unsettled her.

Fear.

They were fearful of her. Why? She was a slender sixteen year old girl. Her hair, dark as midnight, did not grow like the others, those who had ‘normal’ skin and build. Her face was symmetrical, smooth, finely chiselled. Not like her mother at all. True, she had inherited some of her general features, and it was agreed that Faerowyn’s mother had been a particularly attractive women – at least before she had fallen ill.

So she wept, for herself, her loss, her loneliness. She had no doubt the villagers would now seek to banish her, for they didn’t like anything different, and she certainly was.

She corrected herself, wiping the tears away. She was aware of a second figure standing awkwardly at the back of the beach where the shallow pools collected. Here in winter they would not evaporate, and they would remain until the next high tide washed into them. The other was a boy called Markus, just about the only one who did not care about what she looked like, and so received similar treatment from the ignorant village children. Some of them were downright horrible. Markus persisted in trying to be friends with her, even though she had tried to put him off in the past. At least he talked to her, rather than spit on the ground as she passed.

She did not turn round or acknowledge him, but gradually became aware he had moved up alongside her, staring out at the stormy sea, his black, wispy hair whipped about by the careless wind. Her eyes were full of tears so she could not see him clearly, but she sensed he was silent because he did not know how to begin. He wanted to comfort her but had no idea what was needed from him.

She, on the other hand, did not want pity or comfort. Although Markus had been a companion to her for many years, she had not let him get too close to her, not emotionally. She did not understand why this boy had kept on persisting with his friendship, even to the cost of being mocked and mistreated by the others, and she had felt that he deserved better from her. That had then made her resentful, for she did not want to be indebted to anyone for any reason. Best he left her alone. That way she would understand everyone, as opposed to how she felt towards Markus.

She wiped her eyes on her damp sleeves and turned to him. He was still a blur but much better defined. A sniff, another, and she felt the tears were at last stopped. “You don’t need to be here,” she said, her throat painful. The words were forced out.

“I didn’t think you should be on your own.” Markus spoke slowly, thinking about his words. “Just in case one of the others came by to have fun.”

“They have not.” Faerowyn hadn’t seen anyone at the funeral. The ‘burial’ had been swift, the body taken out by boat to the bay and tipped over the side. Faerowyn hadn’t even been permitted aboard; the hastily mumbled excuse that it was dangerous in the stormy seas hadn’t fooled her for one moment. The fishermen just didn’t want her aboard. Bad omen, or something superstitious like that.

So she had stood at this point watching, and it was only when the body had slipped into the sea that the tears had come.

“I am sorry.”

She guessed he meant about her mother. She nodded curtly and looked inland. Mother was at the bottom of the bay, weighed down by a couple of stones, and that was that. No amount of staring out there would bring her back. “I expect they will want me to go now.”

Markus nodded unhappily. “Where will you go?”

“I don’t know. I expect I’ll be eaten by some wild beast. I have no knowledge of what lies outside Selanic.”

“Neither do I.” Markus turned. A foot disturbing a pebble had alerted him and two men were seen approaching, crossing the shallow pools onto the sandbank. “Here come the headsman’s men.”

Faer sniffed again, wiped her eyes fiercely, then looked at the approaching duo. They were the two biggest and toughest men of the village, and as a result were the enforcers of any rule or byelaw the headsman or his councillors brought in. To be truthful, the villagers lived simple, basic lives, hardly impacted by any foreigner or visitor, so rules and laws were nearly always adhered to, and had become custom or tra

dition.

One simply did not go against that.

“Faerowyn,” the bigger of the two said as they reached the two youngsters, “you have been summoned to appear before the Headsman. Please come with us.”

With a shrug she acquiesced; there wasn’t anything else to do. As she stepped in line, noticing that the two burly men gave her space so as not to touch her, Markus followed.

“You are not requested to come, Markus,” the other said, his tone much more neutral, rather than the way the other had spoken to Faer.

“She is my friend, Karvit, so I want to accompany her.”

“You should choose better friends,” the first man said, giving the boy a fierce look. “Anyway, you won’t have to worry about that for much longer. What does it matter? Come along if you wish, but you will not be permitted to speak, as you know.”

Faer glanced at Markus who had gone pale at the sharp way he’d been spoken to, then she sighed and resumed her path towards the headsman’s house. If Markus insisted in attracting their disapproval, that was his decision. How they would treat him when she was gone, she didn’t know, but undoubtedly he would be derided and punished in some pointless and ridiculous way. Markus’ parents had tried for a long time to put him off seeing her but he was determined, if nothing else. For the hundredth time, or so it seemed to her, she wondered why he was so – loyal – to her.

The house was on a rise overlooking the huddled collection of huts and cottages that served as the village, and a winding path led to the front of the residence. It was grander than the other buildings, and possessed the only glass windows. The winter storms had made the constant replacing of expensive glass too much for the poor and simple folk of Selanic. They made do with wooden shutters and nailed-on cloth.

The headsman was seated behind his desk and surveyed the slender, dark girl before him with interest. He glanced once at Markus as the enforcers informed him of the boy’s intention to stand beside his friend, then ignored him. Markus did not count this day. Perhaps in the future he may be of benefit to the community here, but not today, therefore he mattered little.

“Faerowyn, we grieve for the loss of your mother, but we cannot allow our feelings to get in the way of what must be done. You do not have a guardian anymore and so you either need a new one or you must be of use to the community here.”

“I am sixteen, Headsman,” she said calmly.

He frowned, then nodded. “Quite, and therefore technically do not need a guardian. However, your house is needed for a newly married couple – Vambrey and his wife – and the death of your mother has conveniently provided this. You are to move out before tomorrow morning.”

“But I have nowhere else to go to,” she protested, again without any force, for she knew they were merely using it as an excuse to get rid of her. She felt fingers brush her right hand, and then Markus held it. Instead of pushing him away, she returned his grip and stood there, holding his hand gratefully. She fought back tears. She would not weep in front of these heartless people. “What use could I have for the village? Nobody has allowed me to develop any skill; they do not wish me to learn anything.”

“The people here are – uncomfortable – in having one with elf blood amongst them. Too many bad tales are associated with that. I’m sorry, but with nobody willing to take you into their home, you will have to leave.”

“Why? What is bad about elves? What is an elf?”

The headsman shook his head. “I cannot tell you that, nor will anyone else here. You will leave by tomorrow morning, or you will be cast out. It would be best you make a wise choice. Collect what belongings you may have in your home. Anything you do not take will be burned.” He reached down and opened one of the drawers in his desk and withdrew a package of papers tied with string. “I was given these by your mother last year when she fell ill. She asked that they be given to you after her death. I do not know what is contained in them; I suspect they are personal messages from your mother. Here, take them, and be gone.”

Outside she studied the package. It was a roughly wrapped bundle, scraps of old paper and cloth, tied by string three or four times. Clearly her mother hadn’t wanted anyone to see what was contained within it. Her curiosity was aroused. She looked up at Markus who was similarly intrigued, judging by his expression. “Well, I haven’t much time,” she said tonelessly, “I think I should read whatever’s in here.”

“Best to do it indoors,” Markus said, “or the package will get wet.”

She nodded and, clutching the bundle tightly, walked down to the village. Her house was the last on the right, close to the rocks that marked the boundary of the village. Being the last of the row of habitations meant they were rarely disturbed. The house was a simple one. The single door opened to the main living/sleeping/cooking room with a store to one side and at the other end a cupboard. Her mother had never allowed her to open the cupboard, and her final days had been spent in her bed resting against the door to it.

The bed was still there, with the blanket gone – it had been wrapped around her mother’s body when she had been committed to the deep. The mattress of straw was still in place, saggy and worn, but just about the only comfortable place that could be used to sit on apart from her own bed which lay on the rough earthen floor.

Faer’s bed, a shapeless bundle of blankets and saggy cushions – in reality worn remnants of old clothes sewn together and stuffed with last year’s grass cuttings from inland, lay against the far wall and she now sat down on it and peered at the untidy package in her hands.

“Well, aren’t you going to open it?” Markus asked, his eyes filled with excitement. Nothing like this happened in this fishing village at the back end of the known world.

Faer’s mouth tightened with resolve and she set her slender fingers at the knotted string, but it was tied too tightly, and time was wasted searching for the knife used to gut fish and cut bread, but it was finally discovered under her mother’s bed.

With a pounding heart, she slit apart the fraying lengths and the bundle seemed to spring to life, expanding suddenly, released from its prison. Papers fell from clumsy fingers and the two bumped into each other trying to recover them. Finally, all were picked up and the last of the dirty rotting cloth pieces discarded. Shaking, she picked up the first sheet and angled it so that the light from the open doorway fell on the neatly written words.

The first shock was that they were written by her father.

TWO

Faerowyn, this is your father. The words were like a cold shock of icy water being dumped over her. If you are reading this, then I am dead and everything I have tried to avoid has caught up with me. Let me then tell you about who and what you are. Your name is elven, the first part, Faer, denotes you of elven blood, the second, owyn, is of the noble house you belong to, and this is the reason why you are where you are, and why I am dead.

She looked up at Markus who was peering at the words without understanding. “This is my father’s writing!” she whispered, her throat constricted with shock, awe and grief.

“What are those words? They are not our language.”

“You cannot read this?” Faer looked at the lettering, and realised that, indeed, they were not in the language she and everyone else in Selanic used. “What language is this – and why can I understand it?” Confusion made her mind whirl. It was too much for her to take in and the paper dropped from lifeless fingers.

Markus picked it up and stared at the foreign lettering, then shook his head and gave up. “What does it say, Faer?”

She told him. Sobs wracked her. Markus knew she needed reassurance, and he slipped an arm round her and held her to him, concern consuming him. She stiffened, then gave up, flinging herself instead around him and venting all her pent-up sorrow, bitterness, anger and loss.

He lay her down against him and kept the weeping girl wrapped tight, not knowing what to say and deciding maybe it was wise not to say anything. After a long time the crying died down and she l

evered herself up, eyes red and puffy, nose running, cheeks plastered with tears. Markus didn’t have anything to wipe the tears but she did so on her sleeve, and sat up, head bowed.

“Thank you,” she said in a small voice. “I’ve never been held like that except by mother.”

“Sorry,” he said, not knowing why he said that, for he wasn’t in the slightest sorry.

She looked at him, and smiled faintly. “It was kind of you – I’m not used to that.”

“I know. They’re rotten. I’m not frightened because you’re an elf. There’s so many silly stories about elves, all made up by these people.”

“What stories?”

So Markus told her, of the tales of elves eating people, of casting spells on them, of flying through the sky at night to suck blood from their victims, of taking children away from parents to sacrifice them to their terrible gods. There were many other such stories, many of which Markus didn’t need to tell her, for they were variations on the same theme.

Faerowyn looked stunned. Were these stories or were they real? Was she a night-seeking blood drinker? Or would that happen to her now she was sixteen and an adult? Was that why she was being cast out before she changed? Fear stabbed at her heart.

Markus saw the expression. “Silly rubbish if you ask me. Tales set to scare us at night to make us behave! If they were really like that, you think we would have seen them?”

“I don’t know,” she replied, then picked up the papers again, wiped her nose once more, then resumed reading. You, Faerowyn, are a princess of the noble House of Owyn. I cannot tell you where your true home is, for rivals to our noble House have taken power and have exiled all those who would oppose them, and are seeking to hunt every last one of our bloodline down. If they find you, they will kill you. This is why I came this far east, to the very end of the lands, to a place my people – our people – are unaware of.

She translated for Markus’ benefit, and the boy sat entranced, his eyes like discs in the half-light. Before you were born, I fled with my slave girl lover, a human whom had been made captive in my city, and we had fallen in love and I had made pregnant. With you growing inside her womb, we made our way ever eastwards, away from the hunters who would seek to kill all of us. Finally, the time came for you to be born, and we had to stop running. Our boat found the cove of this village, and we were allowed to stay, for nobody turned away a woman about to give birth, even though they clearly did not approve of me.

Casca 43: Scourge of Asia

Casca 43: Scourge of Asia The Lombard

The Lombard Casca 49: The Lombard

Casca 49: The Lombard The Saracen

The Saracen Casca 47: The Viking

Casca 47: The Viking Casca 46: The Cavalryman

Casca 46: The Cavalryman Casca 52- the Rough Rider

Casca 52- the Rough Rider Empire of Avarice

Empire of Avarice The Commissar

The Commissar Casca 45: Emperor's Mercenary

Casca 45: Emperor's Mercenary Dark Blade

Dark Blade The Heir of Gorradan (Chronicles of Faerowyn Book 2)

The Heir of Gorradan (Chronicles of Faerowyn Book 2) Casca 31: The Conqueror

Casca 31: The Conqueror Casca 32: The Anzac

Casca 32: The Anzac The Anzac

The Anzac Casca 37: Roman Mercenary

Casca 37: Roman Mercenary Casca 41: The Longbowman

Casca 41: The Longbowman The Longbowman

The Longbowman Casca 25: Halls of Montezuma

Casca 25: Halls of Montezuma Sword of the Brotherhood

Sword of the Brotherhood House of Lust

House of Lust Casca 39 The Crusader

Casca 39 The Crusader Halls of Montezuma

Halls of Montezuma Devil's Horseman

Devil's Horseman Casca 40: Blitzkrieg

Casca 40: Blitzkrieg Casca 38: The Continental

Casca 38: The Continental The Minuteman

The Minuteman Napoleon's Soldier

Napoleon's Soldier Casca 35: Sword of the Brotherhood

Casca 35: Sword of the Brotherhood Casca 30: Napoleon's Soldier

Casca 30: Napoleon's Soldier The Continental

The Continental The Confederate

The Confederate Roman Mercenary

Roman Mercenary Casca 27: The Confederate

Casca 27: The Confederate Casca 36: The Minuteman

Casca 36: The Minuteman Casca 28: The Avenger

Casca 28: The Avenger The Avenger

The Avenger Prince of Wrath

Prince of Wrath