- Home

- Tony Roberts

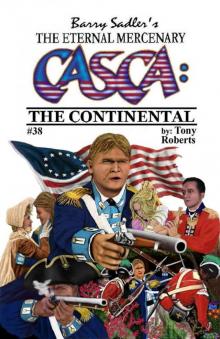

Casca 38: The Continental Page 10

Casca 38: The Continental Read online

Page 10

There were some nods of agreement. People like Ed would fight the war until it was done or it was done with them.

For Casca though, the conflict was assuming a secondary role. Not only was Rose in the clutches of Sir Richard Eley, but Katherine’s life had been thrown into turmoil and was now relying on the charity of Claire Kelly to keep a roof over her head. He ached to get his hands on Sir Richard’s throat.

CHAPTER NINE

The new year brought changes, some fast, some more slowly. A German officer by the name of von Steuben turned up in camp, a former Prussian soldier. Luckily he hadn’t been serving in the same unit as Casca during the Seven Years War, and Casca had kept a low profile from the moment he’d heard von Steuben had arrived. Word was that the Prussian had been a staff officer and eventually an aide to Frederick the Great.

Von Steuben brought a change; like Casca, he believed in drilling the troops and got them all trained in bayonet drill, how to screen on the flanks while the army was on the march, how to maneuver, and how to march faster.

Casca saw the change almost immediately. His unit had been one of the few that had been drilled more thoroughly up to that point, and despite Washington’s support and insistence that the other units follow suit, the brigade commanders were often slow in doing so. Washington could hardly promote Casca above the colonels and brigadier generals, but this newcomer from outside was a different matter altogether. Besides, he had a recommendation from the French Minister of War, and with France about to formally announce an alliance with the revolutionary American people, their recommendations were to be taken seriously.

Washington put von Steuben in charge of training and all units, Casca’s included, were put through their paces. The snow still lay all about, but it made little difference to the schedule. Men were brought together from disparate units and trained, then they were to go back to their units and pass on the information. Officers were grouped and given lessons from the Prussian.

Von Steuben noticed the scar-faced officer in the New Jersey unit. He had the look of a professional about him, and knew what he was about. His men were much better than the others at doing what ought to be done, and the Prussian took an interest in Major Lonnergan. His enquiries surprised him; Lonnergan had served in Prussia’s armies in the war twenty years previously. He could not recall a Britischer called Lonnergan in any unit, but then that was not a great surprise. Many served in armies under assumed names.

He questioned Casca one afternoon after a bout of turning formation from the march to two lines ready to fire. Their breath hung in the still air, a chilly late winter or early spring day, whichever way one looked at it. “Tell me, Herr Lonnergan, which unit did you serve in?”

Casca had dreaded this sort of questioning. He’d served under a different name but von Steuben could still have contacts in Berlin and enquire further. “I served as a private in the armies of Prussia, Herr Major General, seeing plenty of action at places such as Leuthen and Rossbach.”

“Ah, those battles, yes.” A slaughter. The brutality of those battles were still vivid in Casca’s memory. Von Steuben, as one of the king’s aides, would have been there too. “Which unit was it?”

Casca decided to tell the truth; there were so many men at each battle that he reckoned it would be impossible for von Steuben, if he so wished, to look into it. “I was part of Prinz Braunschweig’s unit.”

“We were magnificent, were we not, Herr Lonnergan?”

The Eternal Mercenary nodded. The pre-battle maneuvers that Frederick had undertaken had completely stunned the Franco-Austrians at Rossbach, and even more so against the Austrians at Leuthen, when a handful had been lost as opposed to thousands. In forty minutes the sheer brutality of the Prussian attack had smashed the Austrian left flank. It hadn’t been so much a battle, more like a massacre.

“Perhaps we can so the same with this army, yes?”

“I doubt it, Herr Major General,” Casca shook his head. “You are not dealing with men used to following orders in a military state; neither are we fighting the Austrians. We’re fighting the British who are an entirely different story.”

“But they are led by fools, so I am told.”

“Whatever you’ve been told, Herr Major General, forget it. The British may be led by fools but the ordinary soldier is tough, dogged and vicious. Don’t forget that the vast majority of men in our army are British, either by birth or descent. There is little to choose between the two sides, except the British are better trained and we have better officers.”

“So we train the men better, yes?” von Steuben smiled.

“That will help, but do not expect a Leuthen here. It will be a grind. The longer it lasts the better for us. We’re fighting on home ground while the British have to be supplied over thousands of miles. If the French navy can cut that, then we will be the victors, even if we lose nearly all the battles.”

“All we need to do, Herr Major, is to defeat the British army here. Once that is achieved, then it is all over.”

“Agreed, but I cannot see that happening yet. The men are not as well trained and getting a professional long serving army is not possible; we lose too many men through their ending of their term of service. If we kept them indefinitely, then it may be a different story.”

“Yes, I have seen that as a problem. I shall speak to Herr Washington on that matter. Now, tell me, where did you learn to speak such good German? It is a little old fashioned, but idiomatically it is perfect! No Englischer I have met can speak so good.”

“I’m good at picking up languages, Herr Major General.” It was true, but then Casca had been speaking German for centuries, through all its evolutionary changes. It had left him with a stilted accent and the use of anachronistic words and phrases.

Von Steuben stared at Casca for a moment, then nodded curtly in a very Prussian manner. “As you say. We shall continue our drill tomorrow morning. Your company is very well trained already and should not need too much more to get them up to a standard I am satisfied with.”

So they continued with the training, giving the men something to occupy themselves with while the weather slowly improved and the snows retreated. Casca recognized some of the drill the Prussian was using; he’d clearly read the British army manual. Fight fire with fire, Casca mused.

His unit was proud of the way they received praise from the Prussian. Casca’s hard work with them in the past had not been wasted. Their respect for their scarred commander increased. Whatever he said or ordered, they’d follow. This guy knew his business and was looking out for them. That couldn’t be said for all officers.

France duly declared war on Britain in March and promised men and munitions, but this would take time. As spring came the skirmishing increased on both sides of the river and the Continental Army readied themselves for the new campaigning season. More militiamen arrived to flesh out the ranks of the units denuded of trained men who had gone home, and so the training the units had received had to be repeated again for the benefit of the new arrivals, much to Casca’s irritation.

Another big piece of news that came his way was the replacement of General Howe by the British government. The new man was Clinton who was due to arrive in Philadelphia in May. Casca wondered if that would mean a new offensive by the British, and new tactics. Howe had been good at the flanking maneuver, and now the Continental Army would have to get used to new tactics.

It all promised to be an interesting campaign.

* * *

Major Sir Richard Eley examined himself in the oval mirror hanging from the picture rail in the hallway. He made sure there were no frayed edges to his best parade uniform, or pieces of unwanted material or dust. One had to look one’s best in front of the rest of society.

The parade and farewell party for Howe would be a welcome distraction to the rigors of life in Philadelphia. Supplies had been slow in getting through and Sir Richard had been forced to restrict himself to three banquets a week, an intolerable state of

affairs. The fact the rank and file went hungry much of the time eluded him, but he cared little for that. As long as his household ate, the rest could go to hell.

“Bradbury,” he said, “my wig.”

“Very good, Sir Richard,” the valet-cum-butler said, presenting the item atop a porcelain head-shaped stand.

Sir Richard placed it on his close-cropped head and adjusted it. He examined himself in the mirror once more. “Good. My walking cane, Bradbury.”

Bradbury handed the silver-topped mahogany cane to the baronet and stood back as the Major examined himself once more. “Yes,” Sir Richard said finally, “acceptable. My wife and son?”

“In the drawing room, Sir Richard.”

“Very good. Have my carriage ready in five minutes outside the front, will you?”

“Yes, Sir Richard.”

The baronet walked to the study and entered it, looking at the quiet and subdued figure of Rose seated in the chair by the window overlooking the street. His son, crawling within the confines of a wooden cage, was being watched by the nurse. “I shall be gone for the rest of the day,” he said to Rose. “I would take you but for your ridiculous sympathies. I cannot risk you embarrassing me there. I shall return this evening for dinner. Bradbury will be here to make sure you don’t misbehave and I’ve instructed Corporal McGinnes to make sure nobody enters or leaves the house.” He looked down at her in distain. “You shall learn to accept your place, Rose. As the Lady Sandwell you have a responsibility to me and the title, to behave accordingly. When we return to England I shall ensure you receive the correct tuition. And of course,” he said, placing his tricorn on his wig, “by being in England you won’t be anywhere near this place and its ridiculous notions of self-rule.”

Rose said nothing, and merely looked down at the rug, studying the patterns and symmetry of the design. She could not bring herself to look up at him; he disgusted her that much. The constant beatings and rape had numbed her and she felt more like a piece of the furniture than a person. The only thing that was keeping her sane were the visits by Claire Kelly, in secret, through the servants’ quarters.

Claire had got herself a job in the kitchens as a cook and kept Rose up to date with events outside Philadelphia, and passed messages to and from Katherine. Rose also asked about Casca but Claire said messages from the army had dried up – partly through the hard conditions of winter, and partly through the fact the British had built a line of fortifications north of the city, blocking anyone who hoped to pass.

After Sir Richard had left Rose got up and wandered through the house aimlessly. Bradbury kept a close eye on her, silent, invasive, an uncomfortable dark cloud in her mind. She felt watched wherever she went. The good thing was that Bradbury didn’t know that Claire had been at Katherine’s house, and that Sir Richard had met her. The baronet never went downstairs since he never mixed with the servants; it was beneath his social dignity. Bradbury was the one who did that, and since Claire was only known by her first name, Sir Richard hadn’t picked up on her name when it had been mentioned.

Rose went down to the kitchen, a busy place full of bustling people. The floor was of hard tiles and stone, and the walls free of any decoration. They were stark and functional. The windows let in a fraction of the light that the other floors allowed; being below pavement level meant that the light filtered down through skylights or stairwells.

The kitchen was dominated by a huge open fire with a set of brass pots and pans which were either hanging from the sides or being used to cook or boil food, and an immense solid pine table where the food was prepared.

The other servants bowed at Rose’s appearance, then continued with their duties. Bradbury appeared in the doorway to make sure Rose wasn’t trying to sneak out. Outside one of the red coated soldiers of McGinnes’ squad lounged, blocking the stairwell, eating an apple. Satisfied, Bradbury withdrew and went about his duties.

“I hate that bastard,” Claire said under her breath, eyeing the now empty doorway. “Sneaky little shit.”

“Claire,” Rose scolded her. “Mind your language! If he gets to hear of it you’ll be in serious trouble.”

“He’ll be in serious trouble if he lays a hand on me, I tell ye. Alright, alright,” Claire said, putting a hand on Rose’s arm.

Rose hissed and pulled her arm away. Claire took hold of the arm again and slid the sleeve up. Huge purple welts marked her arm. The Irish woman tutted and took Rose by the hand through to the cupboard, an annex off the kitchen. “How ye stand all this I don’t know.”

“You give me hope, Claire,” Rose smiled. Then she looked sadly at her and a tear rolled down her cheek.

“There,” Claire hugged her. “Don’t let him win. He may beat ye, but ye’re stronger than he.”

“I know. I’ve learned not to say anything. That’s better than saying something. I only get a mild beating instead of a real thrashing.”

“If Case gets his hands on that bastard he’ll rip him to pieces.”

“Oh I wish you could get a message to him! Is there any chance you can?”

Claire swabbed a sharp smelling liquid on the bruised arm and wrapped a cloth around it. “I’ll try but those Brits are everywhere outside. Did you know they’re going to abandon Philadelphia?”

“What?” Rose stared at the dark-eyed woman in shock. “When?”

“Once this new eejit Clinton takes over. Something to the effect now the French are in the war their fleet can cut the supply here. The British navy can’t defend New York, here and the Caribbean at the same time. They’re planning something else.”

Rose looked at Claire in shock. “So how did you find this out?”

Claire smiled. “I hear gossip. Those prigs think a servant has little brains and so don’t understand what rubbish they speak in front of me. Fwah fwah fwah!”

Rose giggled, putting her hand to her mouth. Then she became serious. “But that means we’ll have to leave here! What will happen to me?”

“Don’t worry – I get word to Washington and if I know him he’ll try to stop it. I can’t see the Brits going anywhere other than New York. If they do get there I’ll find ye and do the same there. Don’t ye worry. I’ll write to Case too. He’ll do something to save ye, don’t worry!”

“Oh, Claire, please; I don’t want to stay here another day! And I want my son away from that monster – I’m worried he’ll make him into his likeness. The poor boy is going to be confused enough with me calling him Cass and that monster calling him William George.”

“Leave it to me,” Claire said, squeezing Rose’s hand. “There, that should help,” she said, fixing a pin to the end of the cloth.

“That and keeping my mouth shut,” Rose said in a tired voice. “I hope he stays off the alcohol; he’s even more insufferable when he’s been drinking.”

“What about yer father?” Claire asked, trying to change the subject.

“Oh – in New York running the business, as far as I’m aware. He writes to the monster every week. I’m not that interested, really.”

Claire pursed her lips. “Ye might be better if ye did. Can ye do that fer me? Listen to what yer father says in his letters?”

“Why?”

Claire smiled. “I don’t know, but one day we might be able to use it against them.”

Rose nodded and left the kitchen, her hopes pinned on someone getting her out of the Eley household.

CHAPTER TEN

The British said their farewells to Howe, and General Clinton took over. His first task was to evacuate Philadelphia, his assessment being that the city was untenable and the supply routes too vulnerable. The strategy was to move the war south towards the Carolinas, but first the army had to be extricated from the American capital to New York. His two options were equally hazardous; by sea or by land. The sea route was open to attack from the French fleet and if that happened and the British transport ships were sunk, then the army would be lost and so would the war. So he opted to go by land.

Washington learned of this and immediately gathered his senior officers together for a council of war. Casca wondered what they would do, and whether, if Washington was so inclined, they were up to a battle after the training they’d received.

Colonel Greystock brought the news soon enough. “We’re to attack. The British are abandoning Philadelphia and using wagons and a long supply train. As soon as we know which road they’re taking we’re to hit them hard.” Greystock looked worried; he wasn’t really a man of action but orders were orders. Unlike him, the officers below him looked as if they were delighted. Fists were pumped and shouts of exultation broke into the air.

“Now calm down, gentlemen,” Greystock admonished them. “Go prepare the men for a cross-country march. Lord Stirling will receive his orders in due course and we shall know where to march to at that time.”

Casca returned to his unit and called Soderling and Connors to him. He passed on the news and both looked relived; the inactivity through the spring had gotten them bored, as it had the men. Now they had a chance to show off their new training, and confidence was high.

“What do you think they’ll do, sir?” Lieutenant Connors asked, his youthful face showing excitement.

“What – the British? Looking at the map I think they’ve got two possible routes to take.” He scratched his head. “They’ll have to get to the coast of New Jersey to get across to New York, and they can go either north or south of the Delaware River.”

Connors nodded, flicking out a dog-eared map of the region. He eagerly pressed it down onto a nearby small tabletop and traced his finger across it from Philadelphia to the coast. “The Raritan would have to be crossed if they take the north route, sir.”

Casca peered at the yellowed parchment with its markings. “And they’ll be closer to us if they take that route. And they’ll have to re-cross the Delaware at Trenton.” Casca thought back to the fight at Trenton two winters past. “That would be hard if we’re on their heels.”

Casca 43: Scourge of Asia

Casca 43: Scourge of Asia The Lombard

The Lombard Casca 49: The Lombard

Casca 49: The Lombard The Saracen

The Saracen Casca 47: The Viking

Casca 47: The Viking Casca 46: The Cavalryman

Casca 46: The Cavalryman Casca 52- the Rough Rider

Casca 52- the Rough Rider Empire of Avarice

Empire of Avarice The Commissar

The Commissar Casca 45: Emperor's Mercenary

Casca 45: Emperor's Mercenary Dark Blade

Dark Blade The Heir of Gorradan (Chronicles of Faerowyn Book 2)

The Heir of Gorradan (Chronicles of Faerowyn Book 2) Casca 31: The Conqueror

Casca 31: The Conqueror Casca 32: The Anzac

Casca 32: The Anzac The Anzac

The Anzac Casca 37: Roman Mercenary

Casca 37: Roman Mercenary Casca 41: The Longbowman

Casca 41: The Longbowman The Longbowman

The Longbowman Casca 25: Halls of Montezuma

Casca 25: Halls of Montezuma Sword of the Brotherhood

Sword of the Brotherhood House of Lust

House of Lust Casca 39 The Crusader

Casca 39 The Crusader Halls of Montezuma

Halls of Montezuma Devil's Horseman

Devil's Horseman Casca 40: Blitzkrieg

Casca 40: Blitzkrieg Casca 38: The Continental

Casca 38: The Continental The Minuteman

The Minuteman Napoleon's Soldier

Napoleon's Soldier Casca 35: Sword of the Brotherhood

Casca 35: Sword of the Brotherhood Casca 30: Napoleon's Soldier

Casca 30: Napoleon's Soldier The Continental

The Continental The Confederate

The Confederate Roman Mercenary

Roman Mercenary Casca 27: The Confederate

Casca 27: The Confederate Casca 36: The Minuteman

Casca 36: The Minuteman Casca 28: The Avenger

Casca 28: The Avenger The Avenger

The Avenger Prince of Wrath

Prince of Wrath