- Home

- Tony Roberts

Roman Mercenary Page 7

Roman Mercenary Read online

Page 7

He was broken out of his reverie by a shout from Flavius, who had been peering out across the countryside from the starboard rail. “Riders coming our way! They look like tribesmen!”

All ran to the starboard side, tilting the vessel. The Captain roared at Gunthar and the two Goths to step back and balance the boat. He didn’t want to end up in the river. The fact there was no cargo in the hold made the boat float higher in the water and made it less stable because the weight of the cargo normally negated what went on the deck.

The boat righted itself and Flavius breathed a sigh of relief – he’d seen the waters of the Rhodanus much too close for comfort. He pointed at the group of twenty or so riders cantering towards the river, spears raised, helm plumes flying in the air as they came closer. Casca noted the assortment of helmets and the varieties of armor, and the beards of the men themselves. “Tribesmen, yes. Mattias – are they Burgundians?”

“Ja,” Mattias said, nodding his head. “King Gundahar’s men, no doubt, may the gods rot their scrotums.”

Casca nodded to the cargo hold. “Stay out of sight – if they know who you are they’ll attack for certain.”

Mattias scowled. “They’ll attack anyway – they’ll think we’ve got a hold full of goods. They carry axes, you know.”

“I’m aware of that, thank you,” Casca said, turning back. He shaded his eyes from the sun and stared at the riders. They were fanning out and looking as though they were preparing themselves for a fight. “Gunthar, come here and tell them we’re not looking for a fight; we’re on our way to Lugdunum to pick up a cargo of wheat. Tell them that.”

Gunthar shrugged. “They’ll laugh at that and attack. They see this territory as fair game; the Roman Emperor Honorius has given them the go-ahead to ravage the territory of what he sees as a rival. To them we’re just another ripe fat target to plunder.”

“In that case we’ll give them a fight they won’t expect,” Casca growled. He walked to the captain. “Head to the left bank and moor there. If those vultures wish to attack us they’ll have to cross the river. Are there any crossing points nearby?”

“Upstream about twenty miles,” the captain said, a worried look on his face, but he was already steering to port, increasing the distance from the bank the Burgundians were approaching.

Casca nodded and waved at his men to drop down into the cargo hold. “They’ll be in throwing distance in about three minutes. Get your armor on now, and arm yourselves!”

He landed on both feet, dispensing with the ladder, and grabbed his cuirass, slipping it on with the ease of familiarity he’d gained through the centuries. The others hastily grabbed theirs and fumbled straps and laces through clumsy fingers. Spears were grabbed, swords buckled on, and a couple of axe thongs slipped onto wrists.

Gunthar was still on deck, bellowing across at the riders who had now come as close to the river as possible without falling in, and they carried on riding, keeping pace with the boat. Casca’s ears pricked up at the conversation.

“You are to surrender your vessel to us, Roman scum!” the commander of the scouting party was shouting across the river, some fifty feet wide at this point.

“No deal,” Gunthar shouted back, “can’t you see we’re of the tribes as well here?”

“I care not, to me you’re traitors, having sold your honor in working for these weaklings. Surrender or we will burn and sink you with all on board!”

Gunthar spat into the water. “Well fuck you, then,” he said and climbed down into the cargo hold. “Fucking Burgundians,” he grumbled.

Casca replaced Gunthar by the starboard rail. The horsemen saw that the men aboard had donned armor and were now carrying weapons. They started shouting insults and obscenities at the cowardly crew who skulked over the far side and refused to fight. Casca checked one more time as to what the Burgundians were doing, then leaned over the hold and looked at Mattias. “What are your people doing this far south? Does Gundahar intend moving the entire tribe here?”

“I don’t know,” Mattias shrugged. “They’re looking for a homeland, like all the tribes are, away from the Huns. The trouble is we don’t believe anyone can stop them.”

“The Huns?” Casca replied. He remembered his battles against them when in Persia, and in Kushan. The Persians had called them Hephtalites, but they were one and the same. Evil little bastards, hard, pitiless men. Now it seemed they were heading this way, pushing the tribes ahead of them. He looked at the two Ostrogoths. “Were they the people who caused your flight from your homeland?”

“Ja,” Wulfila nodded, “our kingdom was destroyed and our people had to flee. We lost many in the thirty years or so since this happened. Manneric and I were born during our journey west. The Huns were responsible.”

“Hmmm,” Casca looked back at the Burgundians. Now they were splitting into two equal groups. He watched as the warband leader grunted orders and then they rode apart, one group heading downstream, the other upstream. “Watch it,” Casca said, “they’re up to something.” As he watched, the two groups plunged into the river, each about a hundred yards distant, and the horses began swimming across the Rhodanus. “Shit, they’re going to attack,” Casca said. “Make for the other bank,” he snapped to the captain.

“No time,” the captain shook his head, “the current’s against us and the wind isn’t enough to make headway before they’ll be on us.”

“Then it’s up to us,” Casca growled. “All on deck now! Shields!”

The six other mercenaries poured up out of the hold and took up posts on the port side, shields held ready, swords, spears and axes in their hands. The leading horses clambered onto the west bank, shedding water and shaking themselves, their riders still on horseback, their legs wet. The boat was drifting slowly away from the bank but it wasn’t making enough speed to get far enough away.

The first attack came courtesy of the ten riders up ahead. They came galloping along the bank, sending clods of mud up behind them, the ground drumming with a chest-shaking sound, and as each rider reached the closest point, hurled an axe at the boat. Casca ducked behind his shield as the first one arced towards him, and his shield shook to the blow and the bright, shiny blade appeared through the splintered wood but was held.

More axes flew across the ten feet and struck the rail, shields and mast. Then the second group came up and repeated the attack, but Casca’s men blocked every attack. Then one rider came through the circling horsemen, carrying a rope with an axe tied to the end and whirled it round his head. He flung it sideways as he wheeled side-on to the boat and the axe blade thudded into the bow of the boat.

“Damn, they’re going to pull us into the bank!” Casca exclaimed.

One of the crew ran to the bows, an axe in his hand, intending to cut the rope, but a Burgundian saw him and flung a spear hard that took the crewman through the chest and sent him screaming over the side into the dark waters. The upraised spear shaft floated downstream for a short distance, still attached to the corpse, before sinking out of sight.

The boat turned sharply as the tribesman turned his horse, tugging on the rope, and began to nose towards the bank. “Stay on board,” Casca ordered, watching the Burgundians as they crowded closer, hand weapons drawn, as the boat nudged into the reeds lining the bank. They were much higher than the men in the boat, thanks to their horses and the height of the bank they were on. The only help Casca and his men had was the fact that the bank was thick with reeds and the boat couldn’t get any closer to solid ground than eight feet away. The single rope fixed to the axe embedded in the bow meant only the forward portion of the boat was held. The stern now began to swing out into the river so that just the bows were within reach of the horsemen.

Their leader issued more guttural commands. Casca slapped Flavius on the back. “Take Gerontius and the two Goths and hold the port bow. I’ll take Gunthar and Mattias and hold the starboard. Go!”

The mercenaries scrambled to the front of the vessel just as a dozen of

the Burgundians dismounted and came forward, sliding down the steep bank to the reed beds. Now they were at a disadvantage, having to climb up onto the boat through the mud and reeds. Four of them got to the boat at the same time. Casca hacked down hard at the first hand he saw. He had great delight in seeing the blade of his sword bite into flesh. The victim screamed and jerked back, blood splattering the bows and the reeds.

Mattias and Gunthar waded in, shields forward, blades high. Curses filled the air as men sparred over the rails. Casca shifted his weight to keep balance as the boat shook as two of the enemy grabbed the rail. A shield filled his vision and he hacked down at it. The shield shook to the blow but then pushed back.

“Look out!” Mattias shouted.

Casca looked up and saw a couple of spears arcing through the air. Those still on horseback had flung them in an attempt to drive the mercenaries back. One passed overhead but the second was lower, narrowly missing a tribesman and catching Manneric across the shoulder, sending him spinning to the deck.

Two Burgundians heaved themselves up, dripping water from their bodies, hand axes raised to sweep aside opposition. Casca strode across the deck and slammed his shield into the face of the nearest man. The tribesman fell back into the reed beds. The second man had got to the deck but Flavius turned and thrust his sword between the man’s ribs.

As the German slid to the deck, coughing blood, Casca returned to his position where Gunthar and Mattias were furiously battling against six men. Chips of wood flew as an axe intended for Mattias bit into the rail, and the Burgundian mercenary had to jump back to avoid being sliced open. Gunthar bludgeoned his opponent into the river, but three more swarmed aboard in the space created by Mattias retreating. Casca charged into the fray, sword slicing down. The first tribesman took the blow on the junction of the neck and shoulder. He shuddered as he half turned and fell to his knees. Casca completed the blow and sent another down that drove the point through the man’s throat. It made an obscene sucking noise. Casca pulled his blade free. Another Burgundian came at him. This man had a short sword. Blades met with a sharp ringing above their heads. Face to face they strained, teeth bared. The German’s neck cords stood out as he pushed, but to no effect. With a convulsion, Casca heaved the man backwards against the rail. He cried out as the rail caught him behind the knees and he went overboard, arms flailing.

Mattias was roaring with battle lust, striking down again and again, and his luckless opponent took two blows to the face and chest, and fell back, his tunic a mass of blood.

Suddenly the attack melted away. The five survivors scrambled back up the bank while bodies lay over the deck or in the reed beds, or the wounded slowly staggered away from the blood-soaked vessel. Casca faced the warlord who was sat in his saddle, staring down at the boat in fury. “Now what, you bastard? Want to lose more of your men?”

If he was surprised at hearing a Roman speaking to him in his own tongue fluently, he hid it well. “Dog! Count yourself lucky I do not have fifty men. I would have you tied to the mast and the ship burned in mid-river!”

“If you had fifty men that would mean fifty more corpses at our hands,” Casca countered. “Now get out of here and let us carry on our journey. I’m sure there are more suitable victims for your brave men to get their teeth into elsewhere.”

The warlord was no longer looking at Casca; he was staring in disbelief at Mattias. “It cannot be!” he exclaimed. “You’re dead!”

Mattias spat into the reeds and stood facing the warlord, blood dripping from his blade onto the deck. “So, Hadric, it is you after all. I wondered whether it was you after I saw your pig-ugly snout, as if anyone else in this world could be so afflicted.”

Hadric gnashed his teeth. “This is a traitor to our people, Roman,” he addressed Casca. “Hand him over to us and you can go unharmed. If not, then all of you will die.”

“He’s one of my band; there’s no way I’m going to surrender anyone to you. Now get lost.”

Hadric snarled. “Now we know he is with you there is no way you’ll be allowed to get away. We won’t rest until all of your bones bleach in the sun.”

Casca growled. “Give me one of those spears,” he said to Flavius. The Roman handed him the one that had injured Manneric. Casca weighed it. Good, stout shaft, iron head. Good quality, probably looted from an old imperial arsenal at Mogontiatum or Argentoratum or any one of a dozen cities or towns now lost. He had a sense of deju vu as he lined the weapon up for a throw at Hadric. The memory of hurling a spear at Teypetel, the obese king of the Olmecs, came to him. That time he’d missed, but that was due to Teypetel having the time to see it coming towards him and had dragged one of his captains into its path.

This time the range was ludicrously short. Hadric spotted Casca drawing the spear back and his eyes widened in shock, alarm and terror. He had no time to get out of the way as the spear was hurled with all of Casca’s might. The head punched through his chainmail shirt and tore into his body, splintering ribs and slicing his heart in two. Hadric was sent flying off his horse to crash in an untidy heap of arms, legs and blood on the ground.

The other Burgundians wheeled in confusion and rage. Casca clicked his fingers at Flavius and pointed to the second spear, and the Roman mercenary pulled the weapon out of the deck where it had buried itself and handed it to him. As Casca weighed it in his hand the remaining tribesmen scattered and rode off to a safe distance. Casca grunted in amusement. “Cut that damned rope,” he barked to Gunthar, then turned to face the captain. “Get us away from this bank and back on course for Lugdunum.”

“What about them?” Gerontius nodded towards the dozen or so who remained, riding in the distance.

“As long as we keep them at arm’s length we’ll be able to make our way without much trouble – at least during the day anyway. They may try something after dark but they’ll need light to see their way with, so we’ll know where they are if they do use lights.”

He passed Flavius the spear and watched as the bank receded and the winds caught the sails. The boat began to move back upstream once more. He wiped his blade and slid it back into his scabbard, then squatted next to Manneric who was being tended by Wulfila. “How are you?”

Manneric grimaced. “Sore.”

Wulfila grinned. “He’ll be fine; give him a week and he’ll be as good as new.”

“In that case you’re off sentry duties,” Casca said. “You’re now the cook.”

Manneric scowled.

“Look you dummkopf,” Wulfila cuffed him round the head, “what else can you do? This isn’t a free trip for anyone and being cook keeps you occupied and stops you bitching about your scratch.”

“You have a hole driven into your shoulder, cousin, and you’d shut up about it being a scratch!”

Casca shook his head. “Wulfila is right; I don’t want anyone becoming idle on this voyage. Make yourself useful; the others will have to take your sentry duty, so to stop them from grumbling you feed them. Fair deal, so I think.”

“Yes, sir,” Manneric said moodily.

“Is he always this cheerful?” Casca asked Wulfila.

“Oh yes, he’s been miserable since when his mother shot him out at birth.” Wulfila finished bandaging the wounded man’s arm and shoulder, leaving the limb in an improvised sling. He stood up and nodded at his handiwork, his drooping dark mustache twitching. “We’ve known each other since we were children. Our fathers were brothers, you see, and we were born on the move. As we were of a similar age, we trained as warriors together.”

“So what happened to your people? Your parents?”

Wulfila sighed. “A tribe on the move attracts many enemies. The Romans saw us as yet another threat, especially after the mess your people made at Adrianople a generation ago. The other tribes competed with us for grazing and living land and fights came often. One battle with the Sueves on the far side of the Danube ended with both our fathers dead, and Manneric here and me bloodied for the first time. Our people turned

back but we wanted to carry on, and the tribe split. We were the much smaller group and hunger, disease and fights reduced us to a mere handful. When we crossed the Danube into Roman territory nobody noticed us much since we were so few.”

“And you found your way to Massilia?” Casca finished.

“Eventually, yes. By then only Manneric was with me. The others had settled down, died or gone off to hire themselves to one group or the other. Some even joined the Visigoths of Alaric.”

“Yes, I was with them a short while back,” Casca nodded.

“Ha, so you may have seen them. So, here we are, two refugees looking to find a living in a strange land.”

“Keep your wits about you and you may well find a permanent place to settle down in,” Casca said, clapping Wulfila on the shoulder. He moved off, leaving the two Ostrogoths and checked on the others. None had as much as a scratch, but the captain was much more reluctant to carry on now he’d lost a crewman and had his boat attacked.

Casca stood over him, glaring down at the frightened captain. “You’re to go to Lugdunum; we’ve paid you for passage. If you’re thinking of turning this boat around then I suggest you change your mind. The minute I see you try it I’ll throw you overboard. Got it?”

“Yes, yes, sure,” the man nodded. “Forgive me, good sir. But this boat is my livelihood and if it were to be destroyed I’d lose everything, you understand?”

“I understand,” Casca said, “but understand also that we intend reaching Lugdunum on this boat come what may. You don’t have to come, but this boat will.” He left the captain to his thoughts and rejoined his men, who were busy discussing the fight and commiserating with the luckless Manneric. “The captain doesn’t seem that enthusiastic in continuing,” he said. “Tonight we’ll have three watches of two, one of whom had best stay at the rear to keep an eye on the captain.”

Casca 43: Scourge of Asia

Casca 43: Scourge of Asia The Lombard

The Lombard Casca 49: The Lombard

Casca 49: The Lombard The Saracen

The Saracen Casca 47: The Viking

Casca 47: The Viking Casca 46: The Cavalryman

Casca 46: The Cavalryman Casca 52- the Rough Rider

Casca 52- the Rough Rider Empire of Avarice

Empire of Avarice The Commissar

The Commissar Casca 45: Emperor's Mercenary

Casca 45: Emperor's Mercenary Dark Blade

Dark Blade The Heir of Gorradan (Chronicles of Faerowyn Book 2)

The Heir of Gorradan (Chronicles of Faerowyn Book 2) Casca 31: The Conqueror

Casca 31: The Conqueror Casca 32: The Anzac

Casca 32: The Anzac The Anzac

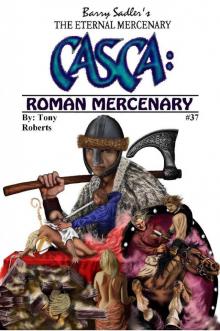

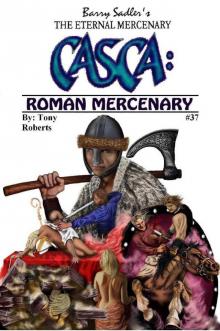

The Anzac Casca 37: Roman Mercenary

Casca 37: Roman Mercenary Casca 41: The Longbowman

Casca 41: The Longbowman The Longbowman

The Longbowman Casca 25: Halls of Montezuma

Casca 25: Halls of Montezuma Sword of the Brotherhood

Sword of the Brotherhood House of Lust

House of Lust Casca 39 The Crusader

Casca 39 The Crusader Halls of Montezuma

Halls of Montezuma Devil's Horseman

Devil's Horseman Casca 40: Blitzkrieg

Casca 40: Blitzkrieg Casca 38: The Continental

Casca 38: The Continental The Minuteman

The Minuteman Napoleon's Soldier

Napoleon's Soldier Casca 35: Sword of the Brotherhood

Casca 35: Sword of the Brotherhood Casca 30: Napoleon's Soldier

Casca 30: Napoleon's Soldier The Continental

The Continental The Confederate

The Confederate Roman Mercenary

Roman Mercenary Casca 27: The Confederate

Casca 27: The Confederate Casca 36: The Minuteman

Casca 36: The Minuteman Casca 28: The Avenger

Casca 28: The Avenger The Avenger

The Avenger Prince of Wrath

Prince of Wrath